Despite in-game ads gold rush, marketers remain cautious

Feature

Compared to TV and cinema, the gaming industry has only recently begun to mature in a way that has opened opportunities for advertisers.

The future of gaming is likely to include many more advertisements.

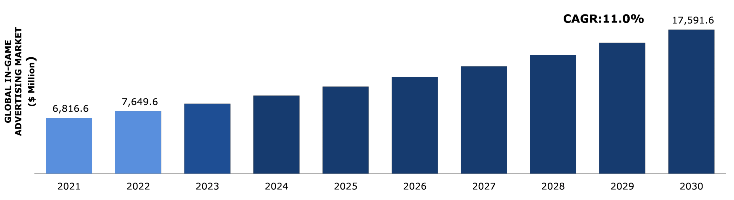

A recent study by Research Dive estimated that the in-game advertising market alone would more than double from its $6.7bn value in 2021 to $17.6bn by 2030, a sign that marketers are itching to increase their foothold in an industry that has for many years befuddled them.

By 2026, the gaming industry as a whole is expected to be worth $321bn, with over 3.2 billion gamers worldwide.

But compared to television and cinema, the gaming industry has only recently begun to mature in a way that has opened opportunities for advertisers, according to Stephanie Hawkins, Wavemaker’s director of sports and live.

“There is a wide breadth of creative opportunities for brands to advertise, ranging from in-game integrations like new skins, maps, and items in games like Fortnite, to custom worlds being built in platforms like Roblox, to more traditional video pre-roll or even playable ads in mobile games,” says Hawkins, noting further than even more “traditional” media, such as running ads on Twitch, can be an efficient way to tap into gaming audiences.

Reaching ‘cord-nevers’ while not being ‘tacky’

With Millennials and Gen-Z comprising an outsized portion of gaming audiences, advertisers are highly motivated to move in.

“For more sophisticated games, we know brands are keen to experiment, as in-game is a chance to get in front of hard-to-reach audiences in an immersive context,” says Enders Analysis head of tech Joe Teasdale.

Hawkins calls these consumers part of the “cord-nevers” audience, as they have drastically different media consumption expectations and desires which have made them more difficult to reach in other media environments like broadcast and ad-free streaming services.

A few early brands have started experimenting in the space. Fortnite, for example, has dozens of character skins from other IPs and brands looking to market to the game’s predominantly younger audience, and brands like NBCUniversal and Samsung have tried their hand at experiential ads in the game. To Hawkins, such developments have built “trust and proof of concept” that allow for more brands to follow suit.

Chart from Research Dive

But Teasdale says that in-game ad formats can still present difficult challenges for marketers.

“[Y]ou either have custom branded integrations that involve huge investment and a high creative bar for one-off experiences, or you’re sticking virtual posters on in-game ad environments.”

He adds: “That looks tacky and there’s none of the attribution you would get with web banners. The data brands get out of gaming platforms is pretty basic: number of visitors to the experience, and from which regions. If you build a custom app then you can measure in-game activity and get the usual analytics, but then you don’t have the built-in audience, and it’s an even bigger development challenge.”

A receptive audience, or ‘acts of vandalism’?

Gamers have long been considered a difficult audience to crack, as they have been perceived as potentially ad-averse.

That may be changing, however. A recent MKTG study found that 55% of esports fans were receptive to sponsors, compared to just 37% of 18-34 year-old sports fans. While not all gamers are into esports and not all esports fans are gamers, the study nevertheless provides some confidence that targeting certain game enthusiasts with relevant ads could be well-received. Though, as Hawkins notes, publishers may be “baffled” trying to decide whether to invest in esports, gaming itself (which involves other questions of which particular platform—i.e., PC, mobile, or console—is best suited to a campaign’s target demographics), or both.

For in-game advertising, platforms like Anzu have sprouted to provide programmatic in-game inventory, placing ads on 3D objects like billboards, racetrack banners, and buildings, as if a virtual extension of out-of-home advertising targeted specifically to various gaming audiences.

“Programmatic allows buyers to quickly run and serve their ads within games, just like they would if they were buying inventory programmatically via any other channel,” said a spokesperson for Anzu. “Prior to this it was very timely and costly to code ads into games. Programmatic has completely changed this.”

Certain ads, especially if they look “tacky”, as Teasdale describes, are unlikely to cut it. And because of the repetitive nature of some games, it is easy to very quickly overload audiences with the same ad. Having an immersive experience interrupted by an awkwardly created, overtly signaled advertisement can be poorly received by gamers.

Some, for example, found Monster Beverage’s overbearing product placement in Kojima Production’s 2019 Death Stranding to be an “act of vandalism”. The placements were removed in the Director’s Cut, which released in 2021.

Similarly derided was insurance company State Farm’s character Jake appearing in NBA 2K22’s MyCAREER mode.

christ pic.twitter.com/js161mB9Q5

— largest rodent (@capybaroness) September 10, 2021

Some players, already inundated by over-monetization in certain games—including in the form of microtransactions and predatory lootboxes—have become cynical about the shifting state of gaming.

Hawkins says that while the gaming audience is generally receptive to advertisements and sponsorships, they are hostile to brand “inauthenticity”.

“Brands that ‘rinse and repeat’ an advertising strategy used elsewhere will usually find it is not well received by gamers,” she adds. “Brands must think about their creative assets through the lens of gaming without going too far as to pander to the audience.

“Usually brands that succeed are brands that understand, celebrate, and often add value to the audience they are marketing to. To do this, brands must understand that they are not advertising to a generic population of ‘gamers’, but to smaller pockets of distinct fandoms tied to specific game titles, game types, game communities, and game platforms.”

Teasdale agrees: “The most sophisticated brands aren’t thinking of social gaming as a paid media channel, but a place to have an organic presence that offers some utility to customers. If you want people to engage with your brand on Roblox, you need to offer them something fun or interesting, or they’ll go to one of the other 40 million experiences.

“If you have a great branded game experience, that can be something you advertise on other channels as a customer destination, and it can even be a revenue generator—just look at Lego.”

Unique considerations for brand safety in gaming

Those distinct fandoms not only mean marketers can target different demographics, but that brands have a broad variety of choice regarding what they are comfortable associating with.

“Usually, we recommend looking at the level of violence and age appropriateness in games,” says Hawkins.

ESRB (US) and PEGI (UK) ratings generally provide fair guidelines for audiences, she adds, with M for Mature games likely having older (though not exclusively) 17+ audiences, compared for T for Teen games that appeal to younger players, such as League of Legends, Fortnite, and Overwatch, and E for Everyone games that are kid-friendly.

Brands must understand that they are not advertising to a generic population of ‘gamers’, but to smaller pockets of distinct fandoms tied to specific game titles, game types, game communities, and game platforms” – Stephanie Hawkins

For games that predominantly appeal to children, Hawkins notes that “advertisers will undoubtedly need to navigate underage compliance issues”, though she points out the development of ‘kidtech’ companies like WPP partner SuperAwesome that are FTC-certified as fully COPPA-compliant.

A spokesperson for Anzu argued that, unlike other popular digital advertising channels, such as social media, gaming offers digital ad environments that are closed, controlled, and transparent, and therefore more likely to be brand safe.

The spokesperson continued: “All the game developers we work with are entirely transparent about the game content, and advertisers have the choice over which titles and even areas of the game their ads are placed in.”

A vast and fast ecosystem

The gaming ecosystem changes quickly. Hawkins explains that what was trendy one week can be boring the next, which provides not only challenges for creatives to keep up, but for media planning and measurement as well.

“While it varies between platforms, assets can be less straightforward than brands are used to, and the quality of measurement capabilities and tracking varies considerably,” she says.

Almost all measurement information comes from game publishers, of which few (if not practically none) allow third party tracking, according to Hawkins.

While “custom branded worlds” like the NBCUniversal and Samsung collaboration in Fortnite should be “fairly easy to see how many players have accessed it”, Hawkins told The Media Leader that outside worlds in Fortnite and Roblox, and trackable video advertisements in mobile apps, “it’s hard to say [how reliable measurement is], as capabilities are so tied to the specific brand integration and game type”.

Potential measurement concerns aside, improvements are coming, says Hawkins, and will make gaming an ever-more appealing playground for advertisers in the near future.

“The projected growth […] will be supported by the evolution of technology. Improvements in games will continue to make game advertising more accessible to brands. Game advertising will continue to be more customizable, more measurable, and quicker to design and implement.”

Just, maybe think twice before you ham-fist an energy drink ad into a game about the apocalypse.