How WPP and NBCU-backed Anzu wants to bridge gaming’s ‘gap’ with marketing

The Media Leader Interview

Itamar Benedy, CEO of in-game advertising company Anzu, hopes to bridge the gap between the needs of marketers and publishers. But can it deliver ads that don’t disrupt gamers’ user experience?

“The stars are aligned in making gaming an advertising category.”

Itamar Benedy, the founder and CEO of in-game advertising company Anzu, has waited seven years for gaming adtech to mature and for advertisers to start recognising the opportunity. But now, he says, it’s here.

“Now gaming is accessible, it’s affordable, easy to plan, easy to transact, and easy to measure,” he says.

Benedy, who spoke to The Media Leader on a call from outside a café in Paris, exuded confidence about the growing market for gaming.

“The brands are ready, the games are ready, the tech is ready, the advertising is ready. Let’s make this a billion-dollar business.”

An example of Anzu’s ad inventory, showing a Samsung ad placed in Slappyball.

‘Gaming was never a bucket’

Anzu was founded in 2017 with the rationale that consumers — especially young, hard to reach consumers — are spending a great deal of time with games, be it on mobile, console, PC or, increasingly, in virtual reality. However, brands and agencies were not keeping up.

“Gaming was never a bucket,” says Benedy, who notes that only recently the medium has received traction from commercial interests and begun to be considered its own advertising category.

Anzu hopes to bridge the gap between the needs of marketers and publishers, and to deliver advertising to games in ways that don’t disrupt or harm the user experience. The company’s headcount has grown to exceed 100, with Benedy leading the global team out of their New York office.

Levelling up: why gaming is the cheat code for modern marketing

Their model is attracting investors. Last month, the company closed a $48m series B funding round; its investors now include WPP, NBCUniversal, Sony, and PayPal. US sports teams are also getting in on the action as they see synergies between live sports and sports video games such as NBA 2K, MLB: The Show, Madden, and FIFA. Parent companies of the MLB’s Chicago Cubs, NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers and Indiana Pacers, and NHL’s New Jersey Devils are also investors in Anzu.

“We see a lot of correlation between sports, gaming, and advertising,” adds Benedy.

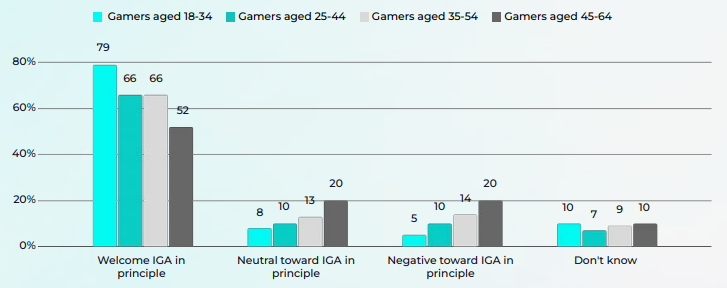

But it’s a balancing act. When asked whether gamers want ads to show up in their games, Benedy admits that there will always be a segment of gamers that hate ads, full stop. But, citing their own consumer research, the vast majority of gamers, especially younger gamers, are either okay with ads, neutral, or otherwise resistant but likely to capitulate over time.

Anzu Survey: Would you welcome more advertisers into games?

Benedy (pictured, below) views in-game advertising as a pragmatic value exchange. While AAA games like this year’s The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom can price their games at $70 without a plan for recurring revenue, the vast majority of games are priced lower or are free-to-play. That means game developers and publishers need to recoup the growing costs of game development in other ways.

Up until now, the primary way to accomplish that has been through in-game microtransactions. Since their widespread introduction in mobile gaming and during the last console generation, they have received lukewarm at best and hostile at worst reactions from gamers, especially if they lead to a “pay-to-win” model where the best in-game materials are locked behind a paywall. Even premium titles like Activision Blizzard’s Diablo IV includes microtransactions, such as allowing players to purchase in-game cosmetic items, as a way to generate additional revenue atop its $70 price tag.

Microtransactions have also at times drawn some scrutiny from regulators concerned with whether purchasing randomly generated items (also known as “loot boxes”) is akin to gambling.

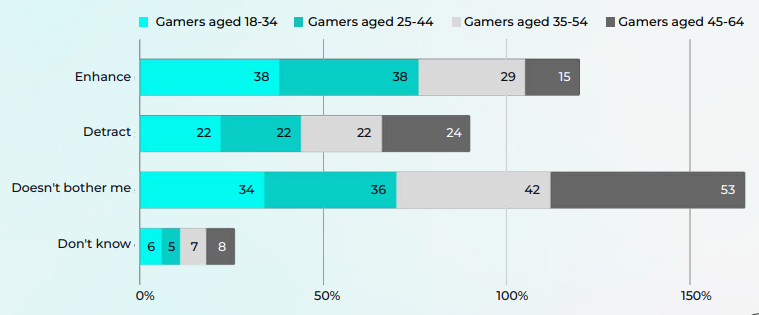

Anzu survey: Do you think in-game ads enhance or detract from the gaming experience?

Advertising, says Benedy, can therefore be a “win-win-win” for publishers, advertisers, and gamers by providing a new revenue stream for publishers and a new way for brands to create incremental reach without having a detrimental impact on gameplay. And, argues Benedy, the placement of ads in games, when done seamlessly, can improve realism. After all, billboards exist in real life, so why wouldn’t players expect to see them in 3D worlds as well?

Anzu works with game developers to create in-game ad inventory that is integrated in an intuitive and seamless way. “It’s really about the user experience,” Benedy says. “If you’re playing a game and there’s a lot of pop ups, like in mobile games, that’s a horrible experience. What we try to do is bring a new way of doing advertising that will actually make sense… We actually make the game more realistic.”

‘However you’re used to measuring other mediums, gaming is going to beat those KPIs in that medium’

On the other end, the company has had to make sure advertisers can easily access in-game ad inventory and purchase it programmatically.

“Brands love innovation. But brands don’t typically change the way they work,” admits Benedy. “So our work is about aligning with existing protocols, best practices, and ways of working in advertising to bring that to the gaming world, versus telling the advertisers to change how they work.”

One of the biggest problems gaming has historically had is that it was isolated from advertising and the digital mix. Anzu seeks to fill that gap by creating a means by which brands can do audience matching, media planning and execution like they would any other digital campaign.

Akin to other digital formats, brands can choose to advertise across Anzu’s inventory at scale on hundreds of games programmatically or through whitelisting specific titles. Advertisers can choose between what ad format they like and upload the creative (e.g., virtual billboards, banners, or videos).

Game publishers, meanwhile, have control over setting up ad inventory, and Anzu’s tech allows for it to be filled with dynamically changing ads that can be programmatically targeted at users based on personalised user data.

Anzu has worked with the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB) and the Media Rating Council (MRC) to create intrinsic in-game advertising guidelines for marketers, and last week announced a partnership with Integral Ad Science to launch a measurement solution to validate in-game advertisement quality.

Current key performance indicators (KPIs) used by Anzu include incrementality, frequency, premium placement, viewability, attention, and attribution.

Rowley: No, the metaverse isn’t dead. Only the incorrect definition

Benedy calls the ad buying process a mixture between digital out-of-home, CTV, programmatic digital, and social. But he believes gaming is a more appealing medium to advertisers like-for-like than those alternatives, because he argues it can out-compete them against their own KPIs.

“However you’re used to measuring other mediums, gaming is going to beat those KPIs in that medium,” he says. “Because in comparison to TV, gaming receives much better attention because there’s no second screen and better viewability because it’s in a 3D world. In comparison to social media, it’s much more brand safe; there’s no user-generated content.

“We’re apple-to-apple showing better results versus other mediums.”

A recent study by attention measurement company Lumen Research, in accordance with Anzu, found that in-game advertisements drive 98% viewability, compared to the 78% average viewability across other digital mediums.

“Gaming is the first ever environment that is 3D and is accessible in a programmatic way,” says Benedy. He adds: “Every game that makes sense to have branded content there, we’ll do it.”