How Gogglebox charmed brands and saved C4’s Friday night

Analysis

It wasn’t an instant hit with Channel 4 or with audiences. But Gogglebox is now a ratings mainstay and a key target for media buyers looking to connect with ‘real people’ for new brand campaigns.

After having written about UK media and advertising for many years now, you begin to appreciate the little ‘a-ha’ moments. When was it that I gained the ability to name all the creative and media agencies that worked on all the ads in a primetime TV ad reel? Or when was the first time I used “programmatic” in a sentence without embarrassing myself?

Another one is to expect your Friday afternoon inbox to be dominated by press releases about a big brand’s new TV spot, set to launch that coming weekend. And Channel 4’s Gogglebox is often the bearer of that first ad launch, when agency and marketing executives eagerly await their new messaging to be seen by ‘real people’ for the first time.

Gogglebox is a show that may sound awful to some on paper: we are invited to watch a TV show about people watching TV and see how they react to the same shows we’ve watched.

But it’s deceptively clever. Even the choice of narrator is deliberate: it was originally voiced by Caroline Aherne, before she died in 2016 and was replaced by her Royle Family co-star Craig Cash. The BBC sitcom centred around a ‘normal’ family whose interactions usually took place while sitting on the sofa half-watching ‘whatever is on’.

The art of curation lies in the cast recruitment and the decision for which shows to feature. The cast, who are approached in the street by talent scouts, watch up to 12 hours of TV a week, usually in two stints, with shows chosen to reflect UK viewing habits. In later series, the TV being watched is just as likely to appear on a streaming platform as it is on free-to-air TV.

Keeping it ‘real’

“It works because it reflects peoples’ experiences back in themselves,” Ian Dunkley, Channel 4’s commissioning editor for Factual Entertainment, tells The Media Leader. “It’s universal in the sense that everyone who watches telly is sat in a room with other people watching telly…. [and] it’s partly about viewers wanting to peer behind the net curtains and see other people’s furnishings, sofas and pictures on the wall as big clues into [learning about] people’s personalities.”

And that conceit of ‘real people’ watching ‘real people’ is exactly what makes it such a favourite starting point for brands to introduce new campaigns to TV, as media buyers and planners tell The Media Leader.

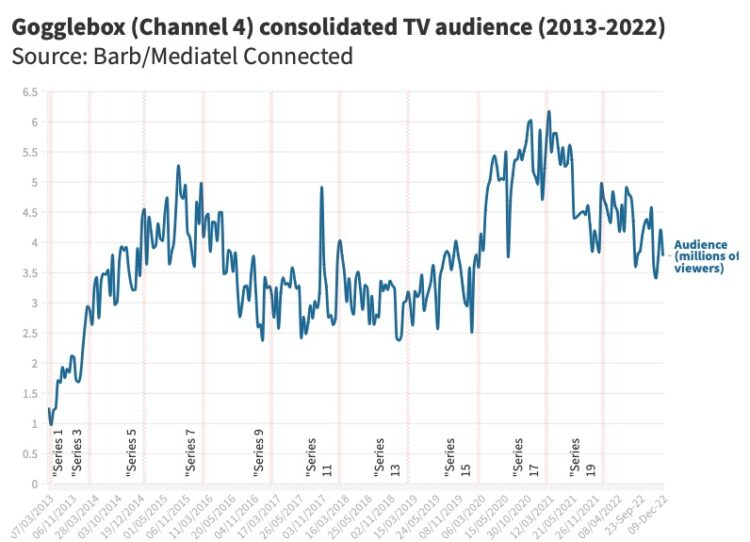

Part of this simply comes down to reaching relatively large audiences. Gogglebox has become a ratings winner for Channel 4 over the decade since it’s first transmission on 7 March 2013. You would have to go back all the way to 2013 to find a year where Gogglebox doesn’t appear in Channel 4’s top-five programmes, Eagle points out. Even more impressively, it has held position one or two for six out of nine of those years.

But, as the data shows, this success wasn’t always the case. Gogglebox was broadcast on a Thursday in its first season in March 2013, attracting between 1 million and 1.2 million viewers across the debut run of four episodes.

In fact, Gogglebox was only ever intended to be a limited series, with creative director Tim Harcourt likening it to a “jolly for six weeks”. Harcourt and Stephen Lambert, CEO of Studio Lambert, pitched the idea of a show called 242 Minutes, with the name Gogglebox tucked away as a backup name (242 minutes was the average time spent watching TV by people at the time, a figure no doubt plucked from an Ofcom report). Channel 4 executives, who preferred the show title Watch With Britain, had originally asked the producers to come up with a 10-minute version.

Later that year, in the autumn, Channel 4 moved Gogglebox to Wednesday nights for 12 episodes, where it fared marginally better with an average of just under 2 million. Over the next six years, it achieved steady audience growth as a mainstay on Channel 4’s Friday night schedule.

The show was given the 9pm slot, once so coveted after a decade carrying episodes of the perennially popular US sitcom Friends and then new free-to-air episodes of The Simpsons, having snatched the Fox-owned animated series from BBC Two after Friends ended in 2004. Then came a period of experimentation under then director of television and content Kevin Lygo: one week there was a Ghostbusters screening, the next a tribute to Ronnie Barker, as well as a failed attempt to score another Big Brother reality-TV winner in the shape of Unanimous.

Brands ‘actively’ ask ads to launch first on Gogglebox

A Friday-night crowd-puller is important. For big brands that need mass audience reach, weekend primetime is almost always the time to launch new marketing activity led by TV. Katy Woodward, strategy planning director at WPP media agency EssenceMediacom, which handles major UK advertisers’ accounts such as Tesco and Sky, says brands “need big ratings winners to build reach quickly”.

“That initial reach [for a TV ad campaign] is absolutely crucial,” Woodward explains by comparing it to how a movie’s success is largely determined by how well its opening weekend pulls in cinemagoers. “Box office sales for the first weekend will determine distribution for the rest of the month. So, if fast reach build for a broad audience is crucial for your market or category, then launching in a weekend is key.”

By series 5 in 2015, Gogglebox was taking in audiences upwards of four million and had clearly hit its stride. At Dentsu media agency iProspect, many of its advertiser clients “actively” ask for a spot in Gogglebox to kick off TV campaigns.

“[Gogglebox] is the ultimate launch pad, driving the coveted shared national cultural moment in time with very little else across the media landscape achieving the same,” Vanessa Eagle, head of investment at iProspect UK, tells The Media Leader. “It creates a halo effect, consistently reaching 20%–25% of the Friday-night TV audience — no other show has maintained this level of reach over the long term — even considering continued fragmentation in the broader AV marketplace.”

It began to create celebrities out of ‘normal folk’ such as Scarlet Moffatt who left to appear on ITV’s I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, has turned her hand at radio presenting, and now features in a BBC show about learning to drive.

But it was in 2020 the show’s popularity hit another level thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic. Audiences soared to between five and six million, which Dunkley attributes to the unique format of the show and the production company’s ability to keep the operation going despite social-distancing restrictions.

“We installed remote cameras in all the houses,” Dunkley recalls. “They were up there permanently, whether we were using them or filming with them or not. So we essentially turned everybody’s living room into a mini studio and then it was monitored from outside in a van. So no one was actually making any human contact or being in the house other than the time when the cameras are installed, when we made sure that everybody was out of the house. And everyone was wearing protective clothing and disinfecting everything. So yeah, it was tricky.”

‘We don’t want them to be celebrities’

Despite its longevity as a Friday-night ratings winner for Channel 4, the 10th anniversary episode is being aired on Saturday (11 March) in a 90-minute special featuring current and former cast members, such as hoteliers Steph and Dom Parker (pictured, below), Sandra Martin and Sandi Bogle.

There are only two sets of stars who appeared in the first episode and are still on screen today: Stephen Webb, who shared the sofa with a number of partners, most recently his husband Daniel Lustig, and the Siddiqui family.

Channel 4 is extremely protective of the Gogglebox brand and actively blocks cast members from doing their own commercial deals.

“We don’t want them to be celebrities,” Dunkley says. “We don’t want them endorsing products. We don’t want them appearing in Heat magazine every day. It’s about keeping them as normal, real, relatable individuals, and the moment they become involved with sort of commercial enterprises, that ceases to happen.”

Eagle agrees that the show would not be as impactful with advertisers if the case did not seem authentic and relatable. She adds: “Viewers enjoy the comedic moments and real-life conversations between the cast and it feels like a safe space for brands. No matter who you are, you will feel represented when you watch these seemingly ordinary people watching TV and commenting on the biggest shows of the week — exactly in the same way you do.”

Nor does the show skew young or old, male or female, ABC1 or C2DE, Eagle points out. “It sits right in the [demographic] middle which explains the pull and why advertisers also keep coming back for more. And for the increasingly time poor, it gives you all your week’s TV viewing in a single, one-hour show.”

Bad news for brands looking to recruit the Siddiquis as influencers, then. Or perhaps not. Woodward remarks that the format of Gogglebox has a particular appeal to planners she’s spoken to because “it looks and feels a little bit like live qualitative testing.”

In other words, viewers that have just spent the last 12 minutes watching other people watch TV could be more responsive to the ad break than if they were just watching a movie or live sport.

“It’s a really odd and interesting media opportunity,” Woodward says. “It’s almost a measure of the effectiveness of your campaign from a brand point of view — being able to understand whether or not people are talking positively about it.”

‘Downward curve? Absolutely not’

As Gogglebox prepares to launch its 10th anniversary episode in the middle of its 21st season, audiences are regressing back to pre-pandemic levels of around 4 million. Dunkley insists his team “fully expected” this.

He says: “It’s not something that’s alarmed us. Over time, it’s grown to, after consolidation, a 4 million [viewer] show. So, with the latest series [21], we’ve had two episodes and they’re on a par with last series. So it’s robust in terms of the viewing audience, it doesn’t feel like it’s for service has been going for 10 years. Does it feel like something that’s on a downward curve at all? Absolutely not.”

What has also changed over time is that 550,000 of that average 4 million is now tuning into Gogglebox on All 4 as opposed to linear TV or catchup. Dunkley, who began commissioning Gogglebox from series 8 and launched the show on streaming, says the show is one of Channel 4’s best streaming performers, alongside The Great British Bake Off and drama programmes. When asked to share streaming numbers, Channel 4 carefully tells The Media Leader that the show is “the third most-viewed unscripted show on All 4 since the platform launched”.

So why, then, are older episodes available on ad-free Netflix (up to Series 16 at time of publication)? Is this is clever distribution ploy to get people interested in the show on another platform and lure them into new episodes on Channel 4 and All 4?

Apparently not, according to Dunkley: “We don’t own these shows. That is part of the slightly weird way that Channel 4 is set up. We’re a publisher/broadcaster, so everything is broadcast under licence. Once that licence expires, then it’s down to the production company to work out where they want to sell it or put it and what the terms are, but I’m not privy to those decisions or those negotiations.”

As for where Gogglebox goes now, there is clearly a reluctance to overhaul the show. “If it ain’t broke, don’t try and fix it,” is Dunkley’s general outlook.

However, it is part of that commitment to delivering ‘authentic’ people on screen that should, in his view, act as an internal engine of evolving the show. As viewing tastes change and television changes, the cast and the things they watch will change, too.

“We’re constantly trying to refresh the cast and find new characters,” Dunkley says. “The truth of the matter is, it’s one of those strange shows where you’re actually looking for people that don’t want to be on it. The reason it works is because the people are, in a sense, unfiltered, they are honest, their responses are genuine.

“They’re not performing for the camera. And they certainly aren’t people that want to be on TV… The most successful cast members are ones that we found not by accident, but we’ve gone looking for them through street casting. That’s why we have the characters we do — they don’t feel like characters that they would necessarily appear on any other sort of long running entertainment show.”