Why people misunderstand this latest ‘Byron Sharp v Binet-Field’ clash

Opinion: Strategy Leaders

Both the 60/40 and 95/5 rules appear to share a family resemblance, but they couldn’t be more different. Marketers and media planners should engage with both rather than choose either one as ‘better’.

If you’re familiar with the term ‘sledging’ you might get the impression that Australians and New Zealanders like to discuss marketing in a spirit similar to how they play cricket. It’s all good knock-about stuff.

And a spicy article about the Ehrenberg Bass Institute (EBI) has gained plenty of traction and barbed comments on social media among the media research and brand marketing community.

To give you a flavour of how the Twitter debate got started, here’s the article’s headline and opening paragraphs, penned by James Hurman who runs a marketing agency in New Zealand:

“It’s not enough merely to win – others must lose: Why the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute’s MO is destructive to the marketing profession. The University of South Australia’s influential Ehrenberg-Bass Institute is back at it again – out in the world denouncing anything marketing effectiveness-related that hasn’t been produced by about 100 of its own marketing science researchers and academics.

“Undermining [the] highly advantageous position we’ve reached together as a marketing community is perverse, and fuels a perception that Ehrenberg-Bass’ priority is not to support our profession in reaching a higher plane of understanding – it’s to confound us, to sow distrust, to win and to make sure others lose in the process, though they needn’t.”

Crossing a line

However, this article crossed an intellectual, rather than a sporting, line and a response was needed. The article is wrong about the motivations of EBI and, perhaps with good but misguided intention, seeks to promote a false industry consensus at the expense of intellectual and scientific rigour in marketing.

Firstly, we should put aside any thoughts of commercial partiality on the part of EBI, which is an academic non-profit institute. Yes, it provides consultancy and sells books but that tends to be the hallmark of all top-flight university departments, whether they be focussed on computer science, engineering or medicine. It’s hard to see how EBI would profit directly from some of its more contentious ideas, such as the primacy of reach in any advertising strategy, without taking a financial position in a media network or proprietary campaign measurement platform.

Secondly, a key theme of the Twitter debate was that EBI was being unnecessarily obtuse in a context where all theories and ideas are converging on the same conclusions in the field of marketing effectiveness. This idea implies there’s little of substance to differentiate all of the theories, metrics and blackboxes competing to measure and explain marketing effectiveness. On the basis of good faith, it’s not a good idea to fudge debate by suggesting ideas are more similar than they appear — EBI obviously doesn’t believe that and continue to argues cogently in favour of its work.

But what really makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up is the idea there’s enough room for everyone to have their own pet ideas or marketing truth — that’s just intellectual nihilism. Rather than settle for some kind of marketing effectiveness Kumbaya, I’d rather see competing explanations fight it out on their testable merits. What we should be striving for is fair competition between competing theories and explanations of marketing, with only the best prevailing.

This point connects to the third and final theme in the debate, which is worth looking at in depth. As one contributor opined, “why [does EBI] take the approach of blanket writing-off any other approaches before they’ve seemingly been tested effectively? Also it’s important to say marketers in the real world require useful, directional guidance grounded in data rather than highly tested exactitude.”

The point about practical utility is well taken — I’m an ex-CMO, run my own business today and appreciate the need for pragmatic solutions to marketing challenges. However, I’ve read enough EBI output to know its academics tend to argue against marketing axioms and heuristics that are essentially unfalsifiable i.e. you can’t test something that can’t be tested and generalised.

From a strictly rational scientific perspective (Rory Sutherland look away now!) relying on unfalsifiable rules of thumb isn’t much different from putting one’s faith in leeches and the placebo effect in a medical context.

A prime example is Binet and Field’s legendary 60/40 rule from the Long & Short of It, which was conflated during the debate with the 95/5 rule formulated by EBI’s Professor John Dawes. In his article, Hurman asks, “why would Ehrenberg-Bass claim that the 60/40 rule is a myth?” and considers it hypocritical of EBI to dismiss the 60/40 rule as unscientific whilst also publishing their 95/5 rule.

Hurman goes on to write: “If Ehrenberg-Bass were as committed to scientific integrity as they claim to be, they would never have published the 95/5 rule prior to applying due rigour. And yet that doesn’t make 95/5 misleading or unhelpful…95/5 is categorically less scientific than 60/40. It wasn’t based on any data and doesn’t conform to any kind of scientific standard.”

One of these rules is not like the other

This is strong stuff, both the 60/40 and 95/5 rules appear to share a family resemblance, if only in terms of simple notation. However, in scientific terms, they couldn’t be more different.

Let’s take the 95/5 rule first, as pointed out to me by Bryon Sharp: “95/5 was John Dawes using a rhetorical device to explain the Negative Binomial Distribution — it’s well established by 50 years of repeated studies.”

Half a century of “repeated studies” is important. The key thing about the 95/5 rule is it makes a clear prediction that is testable and repeatable. The prediction is that on average about 95% of a brand’s customers are not in-market to make a purchase at any given point in time. In other words, only a small percentage of customers (around 5%) are actively considering a purchase of the product or service right now.

The essence of the 95/5 rule is that the vast majority of a brand’s addressable market is not in-market and ready to transact when a brand advertisment plays out — the figure ‘95%’ is an average that simply illustrates what ‘vast majority’ tends to mean. The ‘balance’ implicit in this rule is weighted overwhelmingly towards people not being in market — this aspect of balance cannot be varied, otherwise the rule breaks.

For instance, I’m working on an ad effectiveness study right now. My Nat Rep survey data tells me that about 16% of UK homeowners expect to carry out home improvements or repairs within the next month. Divide that by four weeks in a month, and you get 4% of home owners in-market this week for home improvement or repair services. That means 96% of the addressable market is highly unlikely to convert into a sale following an ad exposure this week.

I was able to test this rule using a random dataset and the rule held, which suggests it applies to many different product categories and is therefore generalisable. This apparently simple, but dependable, rule can have profound implications for any brand’s marketing strategy (the key one being an estimate of how long it takes for a category’s total addressable market to cycle into a purchase moment).

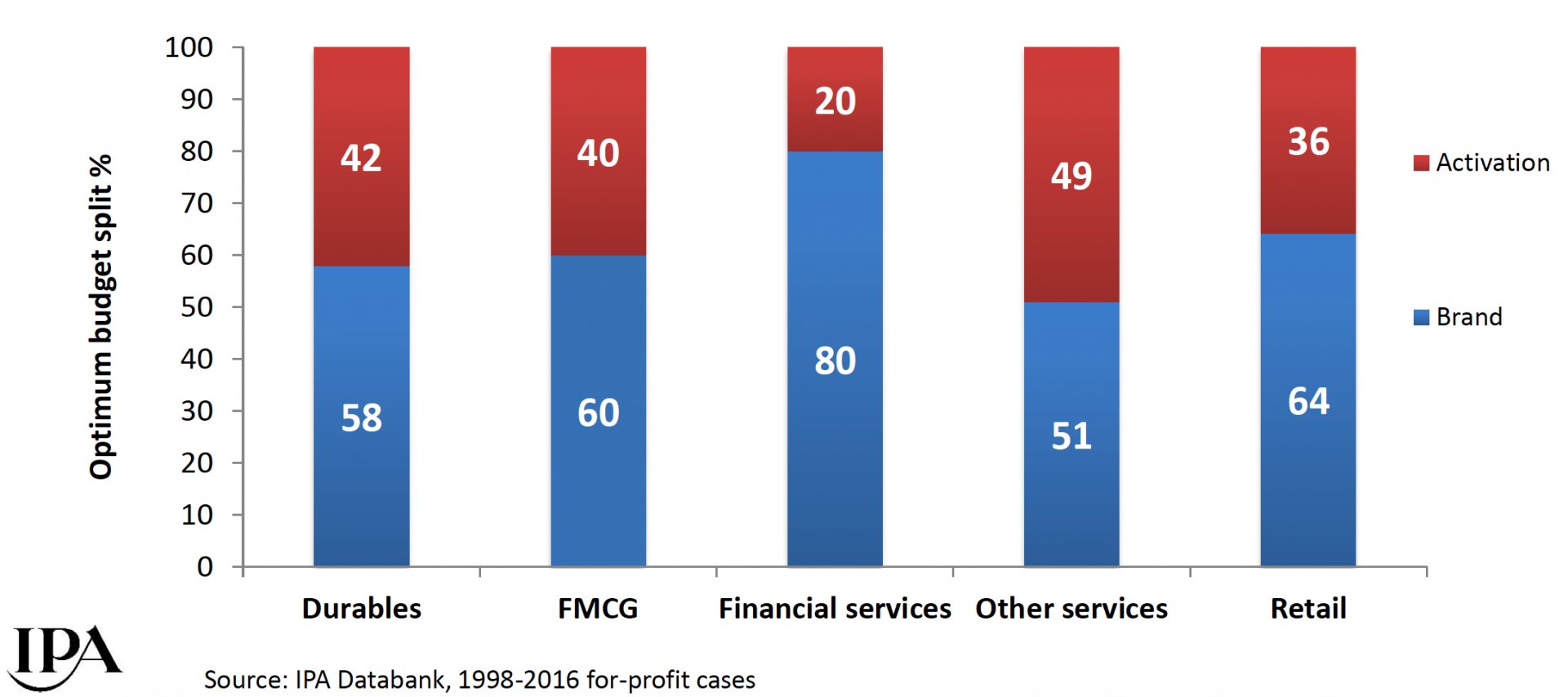

Let’s apply the same thought process to Binet and Field’s 60/40 rule: by investing 60% of a marketing budget into long term brand advertising, you will grow sales/market share/profitability.

The rule doesn’t specify the magnitude of the expected increase in commercial metrics, nor does it define the precise parameters of “long-term brand advertising.” We know that campaigns can vary greatly in terms of audience reach, exposure frequency and creative attributes etc and this ambiguity leaves an awful lot of room for interpretation and variation during implementation.

Additionally, 60% is not a firm rule in itself — the number can vary widely depending on situation, perhaps even tilting the balance in favour of short term activation investment from time to time. As rules go, this is one appears to be highly elastic and easy to vary. In this respect the 60/40 idea is entirely different to EBI’s 95/5 rule, which is very hard to vary i.e. you can’t break the overwhelming balance requirement.

Then there’s the problem of testing. How do I test that the 60% of marketing budget I invested in long-term brand advertising contributed towards an X% boost in sales/market share/profitability? Crucially, how would I disprove the counterfactual i.e. would I have got a better result with 80% invested, or perhaps as little as just 40%?

While econometrics may offer some insights, well-designed experiments using rigorous test versus control procedures are unavoidably necessary to satisfy the counterfactual objection and provide more conclusive evidence of marketing effectiveness.

We need to test theories in practice

To summarise, Professor John Dawes’ 95/5 rule provides a simple yet profound insight into the dynamics of a brand’s addressable market, highlighting that the vast majority of potential customers are not in-market and ready to make a purchase at any given time. Its application transcends product categories, making it a dependable guideline for marketers in developing their strategies.

On the other hand, Binet and Field’s 60/40 rule, while popular amongst practitioners, presents challenges due to its lack of precise definition and its sensitivity to various brand and market contexts. Addressing these concerns would require greater clarity, test evidence and a nuanced understanding of the complexities involved in implementing the rule across diverse scenarios. In its current form the 60/40 idea is simply too elastic to qualify as a general marketing theory with far reaching explanatory and predictive power.

It is important to recognise and discuss the limitations of popular ideas in marketing without attaching negative connotations such as rudeness, cynicism, or a threat to unity within the marketing effectiveness community. Our collective success and the profitability of the companies we represent rely on our ability as media researchers and marketers to engage in rigorous debate, free from biases or preconceived notions.

By understanding both the strengths and limitations of the rules that guide our investment decisions, we can effectively reach and engage with our target audiences, ultimately driving the growth of our brands. Open dialogue and critical analysis pave the way for informed decision-making and continuous improvement in our field.

Jason Brownlee is founder of Colourtext. A version of this article was originally published on his company’s website.

Jason Brownlee is founder of Colourtext. A version of this article was originally published on his company’s website.