On TV, as opposed to traditional print, news broadcasters have had to compete with other entertainment options and design newscasts around minutes-long ad breaks. On Twitter, journalists have had to limit their communication to 280 characters at a time (or 140 before 2017).

And now on TikTok, newsbrands are experimenting to strike a balance between delivering the facts and retaining the attention of young users in a format that most expect to be comedic or entertaining.

According to the latest report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and the University of Oxford, 81% of British newsbrands and 77% of American newsbrands now operate accounts on TikTok.

Recent surveys have found that while a quarter of under-30s report regularly getting news from the platform, its youngest users primarily view TikTok as as a platform for entertaining comedy and humour.

For news outlets, that is creating a challenge for how to meet young audiences on their own turf.

Clodagh Griffin, a journalist at digital and social media-focussed news startup The News Movement, told the Reuters Institute: “The first three seconds on TikTok is literally the most crucial. I guess it’s like the modern-day headline.” She added that the pace of videos needs to remain fast, with quick jump cuts and no pauses for breath.

“The attention span is super, super short,” described Larissa Eberhardt, head of social media for Austrian regional news outlet Kleine Zeitung. “We sometimes struggle with the fact that we can hardly ever enrich the content because the videos need to be so short.”

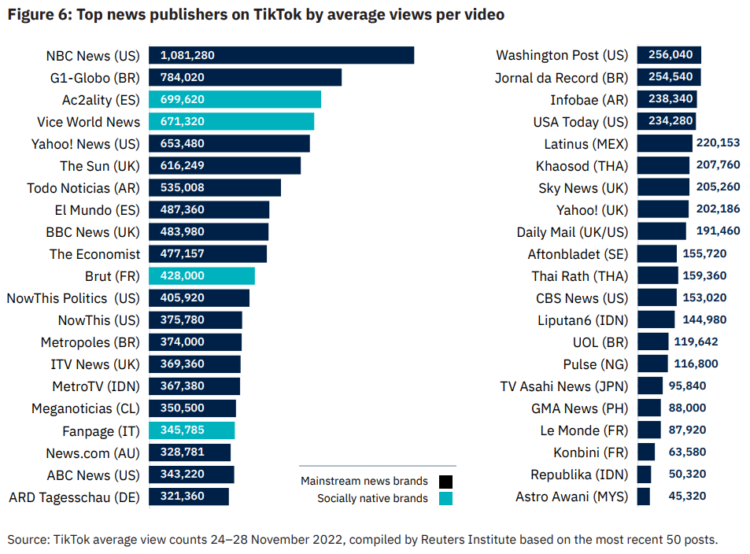

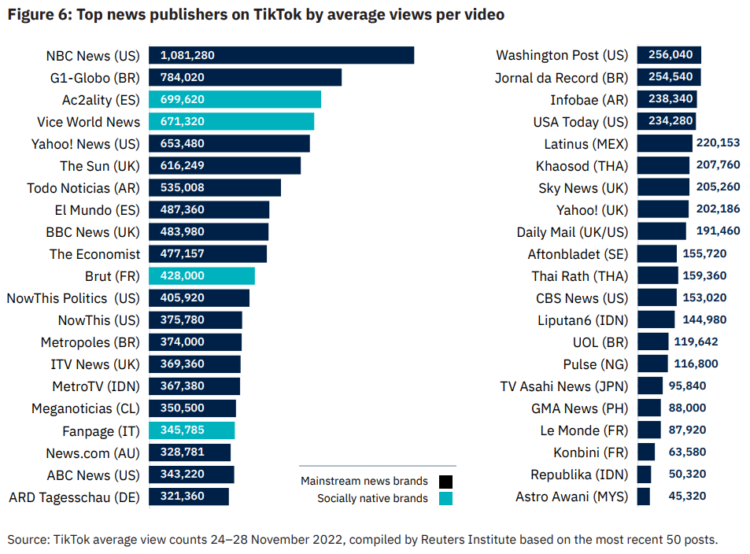

Unlike other digital platforms like Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube, where follower/subscriber numbers are required for success, TikTok’s algorithm-based drip of content means that average views per individual video is a better way to measure success on the platform than subscriber count.

Case in point: whereas the Daily Mail (4.2 million) and Sky News (3 million) have the most followers of UK newsbrands, The Sun, the BBC, and ITV News typically average more views. As such, content truly is king on TikTok, more so than necessarily brand.

Memes and jokes also often take precedence when competing for that “short” attention, and relating to younger audiences is paramount to success.

The report described a variety of strategies newsrooms are toying with to achieve success on TikTok, including working with existing creators to TikTok-ify their reporting by mixing humour with substance.

Dave Jorgensen, a TikTok creator recruited to make posts for The Washington Post, noted: “you need to think like someone who creates TikToks. You shouldn’t think like someone who’s made videos for Facebook or for YouTube. It’s very specific.”

No dominant strategy appears to have yet been developed; some global news organisations, like WaPo are using creator-led content, others like The Economist are brand-led. Some, like The Los Angeles Times‘ puppet-hosted ‘Sorry Report’, are leaning more into entertainment, others are keeping things mostly informative.

Grabbing attention within the opening one to three seconds, using easy-to-understand language, and having a “light touch” were described as overarching themes that news organisations were needing to hit on to have success with audiences.

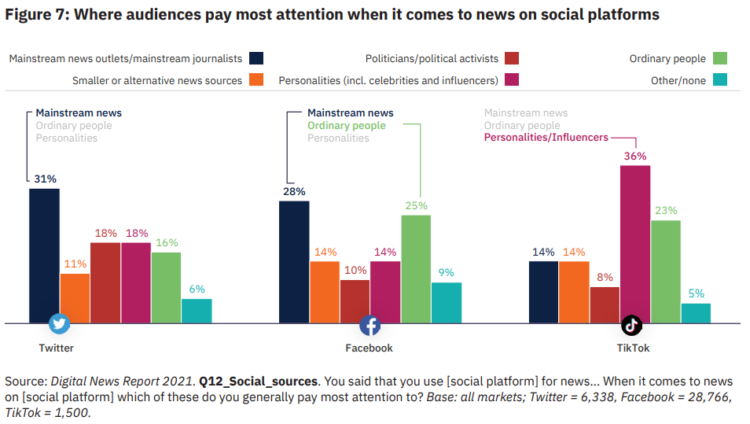

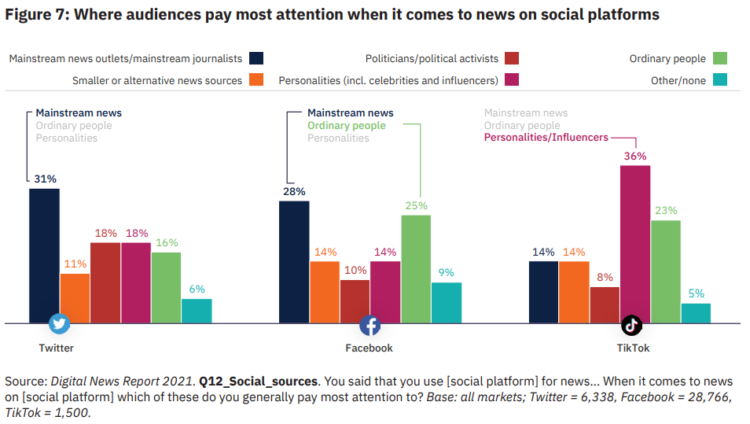

Trusted journalism has an uphill battle on TikTok, where audiences pay much greater attention to personalities like celebrities and influencers for news than on other platforms like Facebook and Twitter. According to the Reuters Institute’s 2021 Digital News Report, just 14% of users pay most attention to news on TikTok from news organisations themselves. Rather, a plurality (36%) say they pay attention to personalities/influencers. That is a far cry from journalists’ relative dominance over extant platforms Twitter and Facebook.

This has been caused in part by the relatively slow adoption from major newsbrands and their journalists of a large footprint on TikTok. The void for news and information has instead been filled by creators and activists, who may not have the same level of resources or accountability as a major newsroom.

That may be cause for additional concern for a platform that already has been proven to struggle with detecting misinformation.

According to the report, major publishers would like to see more support from TikTok to promote their high quality journalism, such as through a dedicated space for news on the app from verified sources. Additional tools for audience measurement and monetisation are also on the wishlist.