Attention elasticity: the Attention Economy’s chicken and egg question

Opinion: Attention Revolution

Does the creative or the media platform drive and hold your attention?

How can an egg come first when a chicken needs to hatch it? How can a chicken exist without being hatched from an egg?

The answer to the age-old argument may depend on which side of the principles of evolutionary biology you stand. Thankfully, there’s no need to keep brooding.

Science has finally unscrambled the riddle. And the winner is – the egg!

Apparently, and in simple terms, eggs have mutated within embryos over time until the chicken eventually became a chicken which eventually laid chicken eggs.

Fast forward to the attention economy and the main driver of attention to ads, and a similarly circular debate is happening.

Does the creative catch your eye and determine how many seconds of attention you pay? Or does the platform set the rules?

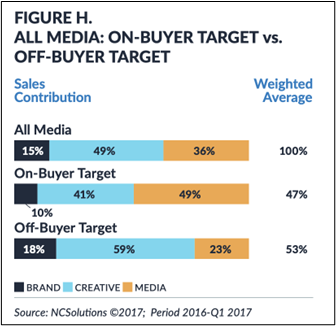

A highly cited article from Nielsen in 2017 on the proportion of brand sales lift coming from the creative has set the tone.

Nielsen suggested that more advertising effectiveness comes from the elements of creative (49%) than media planning characteristics such as targeting and reach (36%).

Admittedly, this did come with the caution that creative’s reign as king is under pressure. I would argue that in the five years since this paper was released the tide has truly turned.

When looking at the influence of creative versus media we moved the argument away from blanket reach and turned to attention paid. We did this because we know that reach is an inequitable cross-media metric.

The Nielsen figure below shows the percentage of contribution to sales – creative vs media.

Problem is, because they have used reach (an inequitable metric) it could have easily unbalanced the sample frame at the ‘on-buyer’ versus ‘off-buyer’ level.

If the off-buyer target group paid less attention, but the reach was considered equal to the on-buyer target group, the results of this study could be vastly different.

Considering attention, not reach, and placing controls to ensure the same creative is tested across different platforms, ensures the influence of media is better isolated and captured.

In dozens of sets of data, we see that the same creative performs worse/better in line with the overall attention performance of the platform. This means that even good creative is impacted by platform performance.

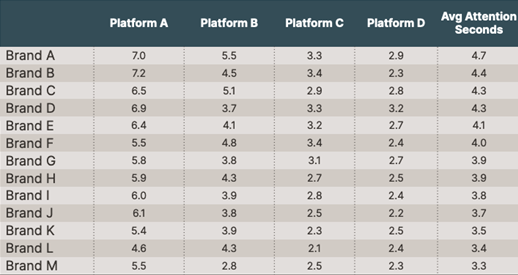

In Figure 2 (below), Brand A has the highest attention paid overall, and is therefore defined as ‘good’ creative.

But look at the declining amount of attention paid across different platforms.

So, let’s look at Brand M which has the lowest attention paid overall and can be defined as ‘weak’ creative. It suffers the same decline in attention across different platforms.

This is the impact of media over creative.

If creative was the dominant power the same creative would display highly similar amounts of attention across all platforms. It doesn’t.

If creative was the dominant power you wouldn’t see the same systematic decline across both good and weak creative. But you do.

Why is this happening?

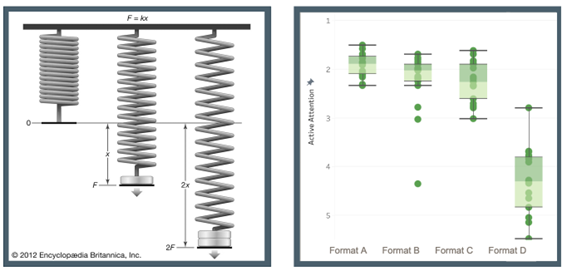

It is happening because of what we call Attention Elasticity – the range of attention seconds possible under the conditions of that platform or format. Attention elasticity forms the attention opportunity for ad creative.

Think of it like the upper limit of attention seconds typical by platform and format.

We know that each platform and each format has its own elastic attention limit, which is directly moderated by the functional performance of the platform.

For example, scrollable formats are less elastic, the range of attention they offer is not as great.

Others, with less distracting features, are more elastic and the outer range of attention they offer is greater.

When the attention elastic limit is small, the ability for creative to work outside the attention norm is low.

Think about it like physics, where the elastic limit depends on the type of material considered. A steel bar can be extended only about 1% of its original length, but rubberlike materials have elastic extension of up to 1000%. The reason sits in their very different microscopic structures.

Attention elasticity has huge implications on creative strategy and performance. It means that ad creative has little chance to shine outside these boundaries which are set by the functional structure of the platform.

The best ‘good’ creative can be expected to achieve is the top of the attention limit of that platform or format.

If creative was the dominant power we wouldn’t see systematic attention elasticity limits – but we do.

This work is yet another affirmation that reach across platforms is inequitable.

The negative flow on effects of this inequity are systemic in any concept, market mix modelling or strategy that relies on equitable impressions as an input variable.

We can thank evolutionary biology for giving us the ‘egg’ answer. And we can thank objective science and attention metrics for answering advertising’s own chicken and egg puzzle.

It’s media first all the way.

Thank goodness it didn’t take 58,000 years to figure that out.

Professor Karen Nelson-Field is a media science researcher and founder of Amplified Intelligence.

Attention Revolution is a monthly column for The Media Leader in which she explores how brands can activate attention to measure online advertising as well as build a better digital ecosystem.